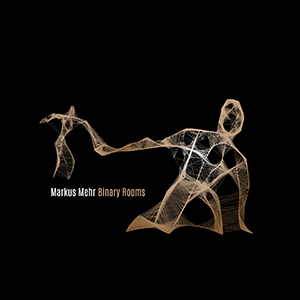

Hidden Shoal’s Matthew Tomich spoke with Markus Mehr about his new album Binary Rooms, phonography and the art of sound.

Under his solo moniker, Markus Mehr has made a career out of patterns. Before the release of his fifth record Binary Rooms last month, his last three albums – a triptych of interconnected ambient/drone records, beginning with IN in January 2012, ON 6 months later and concluding with OFF in January 2013 – were exercises in sonic ritual, building upon repetitions of harsh electronic noise, warm synths and ethereal sound manipulation. But on Binary Rooms, Mehr’s new preoccupation is with duality and the relationship between opposites: warm and cool, organic and synthetic, reality and fiction. Part of that latter juxtaposition comes because much of the material on Binary Rooms began as field recordings.

Under his solo moniker, Markus Mehr has made a career out of patterns. Before the release of his fifth record Binary Rooms last month, his last three albums – a triptych of interconnected ambient/drone records, beginning with IN in January 2012, ON 6 months later and concluding with OFF in January 2013 – were exercises in sonic ritual, building upon repetitions of harsh electronic noise, warm synths and ethereal sound manipulation. But on Binary Rooms, Mehr’s new preoccupation is with duality and the relationship between opposites: warm and cool, organic and synthetic, reality and fiction. Part of that latter juxtaposition comes because much of the material on Binary Rooms began as field recordings.

“I didn’t sit down and play a piano or play the guitar and see what’s coming out of me,” Mehr tells me over Skype from his home studio in Augsburg, Germany. “So it’s more a collecting kind of thing. Then you start out and play around with things. It’s more that a sound or a recording or a noise attracts me, and I want to find out what is it and what can I do with it. Can I extend it? Can I slice it? Can I trash it or can I refine it? Like everybody who does field recordings I always put my ear on things to find a spectacular sound. It could be a car that drives by my window. It could be my cat. He’s snoring and that’s a beautiful sound. And after that hunting, a lot of editing and processing follows up.”

“I’m basically a musician, but on Binary Rooms, most of the time I did non-musical things. I see myself nowadays as more of a phonographer. I look at what’s outside and what’s surrounding me. That’s maybe where the whole thing starts. ‘Gymnasium Swarms’ starts with a sound from my kitchen. So you can hear my heater here. It’s a very spooky sound.”

The result of Mehr’s new found interest in field recordings and found sounds is a record that’s diverse and brimming with aural contradictions. The eight tracks on Binary Rooms offer so much variation that it’s impossible to settle upon a mood for more than a single composition. Opener ‘Buoy’ is 2 minutes of claustrophobic and uneasy listening, littered with sparse and unsettling sounds that sound as though they could be metal scraping against metal, the plucking of an out-of-tune violin or something else entirely. It’s followed by ‘In The Palm Of Your Hand’ which marries pulsating synthetic percussion with a somber piano riff and street ambience, before the harsh glitches of ‘Pedestrians’ strike like an electric shock. What Mehr appears to be doing on Binary Rooms is inhabiting a creative space that situates him somewhere between composer, phonographer and assembler of the aural world around him.

The result of Mehr’s new found interest in field recordings and found sounds is a record that’s diverse and brimming with aural contradictions. The eight tracks on Binary Rooms offer so much variation that it’s impossible to settle upon a mood for more than a single composition. Opener ‘Buoy’ is 2 minutes of claustrophobic and uneasy listening, littered with sparse and unsettling sounds that sound as though they could be metal scraping against metal, the plucking of an out-of-tune violin or something else entirely. It’s followed by ‘In The Palm Of Your Hand’ which marries pulsating synthetic percussion with a somber piano riff and street ambience, before the harsh glitches of ‘Pedestrians’ strike like an electric shock. What Mehr appears to be doing on Binary Rooms is inhabiting a creative space that situates him somewhere between composer, phonographer and assembler of the aural world around him.

“[On Binary Rooms] I’m doing collages and putting things together to try to arrange new levels and new worlds,” he explains. “I try to redesign realities. I try to redesign reality in itself – maybe from A to B, you make C. To try to bring things together that usually don’t belong together – that’s exciting.

“For example, ‘Basin of the Lost’ is based on underwater recordings where all these really sad fishes swam in a tank, ready to become a burger or wha ever just a few hours later. And during the editing of the track, I don’t know why, but I thought a helicopter sound would be great. So in the real world these two audio events don’t belong together, but in the track – I mean, it makes sense somehow, and it keeps the whole thing weird and narrative. That’s the kind of work that interests me most right now.”

At 86 seconds, the track ‘Blackbox’ feels like an interlude, but buried beneath its oscillating synths is a fascinating subtext. Mehr initially began working on the then-unnamed song in 2013, and found himself applying some finishing touches on July 17, when less than a day’s drive from Augsburg, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was downed in Ukraine, killing all passengers on board. Though the title was eventually changed to ‘Blackbox’, Mehr initially named the track ‘MH17’ as a means to force himself to remember the tragedy.

“I had no title for that track,” he says, “and I thought, we have so much news – so many things around our head every day – and if we are honest, that tragedy is almost out of our minds right now. And it was very personal, because I’ve tried to make a mark in my mind that it happened while I was working on that track. There are so many tragedies we have to see on the screen and after two or three days they’re gone. I wanted to make sure that this one doesn’t go out of my mind anymore.”